See menstrual artifacts from ancient Peru (bowl as bleeding vulva); Almora, Uttar Pradesh state, India; Rajasthan state, India; 19th-century Norway; Italy; and instructions for making Japanese and German washable pads from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.See covers of Growing Up and Liking It booklets - ads for teenagersRead most of a 1928 Australian edition of Marjorie May's Twelfth Birthday. Marjorie May's Twelfth Birthday (1935) - Facts About Menstruation that every Woman should know (1936) - Marjorie May, introductory page, 1935 main pageRead Lynn Peril's series about these and similar booklets! And see the covers of the booklets How shall I tell my daughter?, Growing up and liking it, and Personal Digest; read the whole booklet As One Girl to Another (Kotex, 1940).Marjorie May, three booklets, 1935 main pageRead Lynn Peril's series about these and similar booklets! And see the covers of the booklets How shall I tell my daughter? and Personal Digest; read the whole booklet As One Girl to Another (Kotex, 1940).See a Kotex ad advertising this booklet.See Kotex items: First ad (1921; scroll to bottom of page) - ad 1928 (Sears and Roebuck catalog) - Lee Miller ads (first real person in a menstrual hygiene ad, 1928) - Marjorie May's Twelfth Birthday (booklet for girls, 1928, Australian edition; there are many links here to Kotex items) - Preparing for Womanhood (1920s, booklet for girls; Australian edition) - 1920s booklet in Spanish showing disposal method - box from about 1969 - "Are you in the know?" ads (Kotex) (1949)(1953)(1964)(booklet, 1956) - See more ads on the Ads for Teenagers main pageDIRECTORY of all topics (See also the SEARCH ENGINE, bottom of page.) CONTRIBUTE to Humor, Words and expressions about menstruation

and Would you stop menstruating if you could?

|

Dress, Gender and the Menstrual Culture of Ancient Greeceby Amy Pence-Brown

Introduction Following the fashions of the female menstrual flow and its culture throughout time is a difficult task as its importance, artifacts and documentation were until relatively recently scarcely interpreted or acknowledged. This is especially true of some of the oldest civilizations we can trace, that of the Egyptians, Romans and ancient Greeks. Within the last thirty years women's history, previously discounted or ignored, has sparked scholarly interest especially in the area of ancient Greek women's social and private lives. This information is usually obtained by analyzing the objects of the civilization that remain, mainly art works, texts and artifacts. By utilizing all of these sources this paper focuses on the dress and gender roles associated with ancient Greek women's menstrual culture through the female's various life stages: the cult of Artemis, menarche, the "illness of maidens," death, marriage, defloration, conception, giving birth and menopause. The aspects of dress surrounding menstrual culture have been chiefly understudied in ancient Greece, as well as today, yet there is much to be learned by examining and analyzing them. In doing so it is important to identify what constitutes the unique dress of menstruation, list the sources and texts examined, compare and contrast our modern menstrual dress and culture and the way it is being preserved for future generations using the Museum of Menstruation as an example and tie our traditions to those of ancient Greece in order to think both broadly and critically about the topic. [NB: I unfortunately could not include most of the illustrations in the paper because of reproductive quality and/or copyright concerns. I hope to illustrate Pence-Brown's points in the paper before the year is out, after I retire; I'm an illustrator.] Definition of Dress According to an article titled "Dress and Identity," dress theory scholars Roach-Higgins and Eicher define the dress of an individual as: An assemblage of modifications of the body and/or supplements to the body. Dress, so defined, includes a long list of possible direct modifications of the body such as coiffed hair, colored skin, pierced ears, and scented breath, as well as an equally long list of garments, jewelry, accessories, and other categories of items added to the body as supplements.(Footnote 1) Sebesta, another scholar of Greek women, writes: Textiles, in fact, marked many stages in a woman's life and these stages all focused on a woman's reproductive status. Mothers dedicated richly woven textiles to Artemis after their daughters had successfully experienced menarche and to birth goddesses after a successful childbirth. Family members dedicated beautifully woven dresses to Iphigeneia at Brauron on behalf of women who died in childbirth.(2) Occasionally utilizing the more traditional aspects of dress including everyday garments, costumes and jewelry, the menstrual culture of Greece primarily lends itself towards more non-traditional yet valuable aspects of appearance such as nudity, beliefs about the body, suppositories, adhering items to the body, ingesting items into the body and hand-held objects, sometimes in the form of dedications to the goddess Artemis.(3) In an earlier article on dress Eicher and Roach-Higgins address these unusual types of dress as problems with classification and terminology and therefore broaden the definition: We also take the position that the direct modifications of the body as well as the supplements added to it must be considered types of dress because they are equally effective means of human communication, and because similar meanings can be conveyed by some property, or combinations of properties, of either modifications or supplements.(4) Sources and Texts Although the artifacts depicting dress and the menstrual culture of ancient Greece are scant, texts offer the greatest insight. Ancient written sources include plays from the period and inscriptions on artifacts but mainly consist of medical texts written by men. A few of the well known, well preserved and well documented include Diseases of Women, History of Animals, Gynecology and On the Natural Faculties. As a portion of the Hippocratic corpus, Diseases of Women focuses on female menstruation and is part of a group of medical writings attributed to the legendary father of Greek medicine, Hippocrates, but was later discovered to be composite writings of male physicians studying his medical theories in the fifth century BCE.(5) Aristotle wrote the History of Animals in the fourth century BCE, describing the bodily layout and functions of all animals and thus connecting humans.6 Soranus, a Roman physician in the first and second centuries CE, wrote an entire treatise on female medical conditions titled Gynecology which greatly concerned itself with the role of the midwife in ancient culture.(7) Galen, a physician and philosopher, lived and wrote On the Natural Faculties, a medical text occasionally discussing menses, during the second century CE.(8) Current books and journal articles, written mostly by female scholars since the 1970s, provide valuable interpretations of menstrual dress in these ancient medical texts and often decipher related images such as vase paintings, statuary, architectural remains, textiles and other artifacts, like mirrors. [Bibliography. More bibliography on this MUM site.] In an article regarding the use of male-composed medical texts as a source for ancient Greek women's history, King warns of the limitations as well as cites the positive aspects of them by asking questions such as, "Is it possible to recover women's ideas and experiences from male-authored texts, and if so, how should we go about doing this?"(9) It is probable that medical texts are sources of realistic practices and that these authors acted as reporters, recording remedies, stories and feelings passed on between generations and told to these writers by female patients, hetairai, or Greek female sex workers, and midwives. Menstrual medical writings are more likely to represent the true voices of women as men did not experience menstruation nor were they very often involved in the physicality of it as physicians, therefore, the written accounts were probably obtained through women.(10) These limitations and values can also be applied when looking at artwork and artifacts as they often represent views filtered through the artist's eye which was most often that of a man. Stages of Modern Menstrual Dress Now that dress has been defined and the sources identified it is important to classify the menstrual dress and culture of the modern American female first as an interesting tool to recognize similarities, differences and biases to that of ancient Greek menstruation. Today girls can "get their period," the most popular modern term for menses, as young as eleven years old and soon develop a monthly pattern of doing so. There are no significant rituals leading up to this except perhaps the mandatory short film introducing females to menstruation in the fourth grade. Exteriorly no noteworthy changes in dress accompany this physical change except perhaps the carrying of a purse or a trendy case for the first time in order to conceal the transportation of maxi pads or tampons. Pads adhere to the underpants and tampons are inserted into the vagina by hand. The shaving of body hair and the wearing of nylons, makeup or a bra may correspond in time with the beginning of menses but not necessarily as a result. Menstrual discomfort is most often alleviated with over-the-counter medication and new technology provides items like the Playtex Heat Therapy Heat Patch, which sticks to the abdomen or lower back, can be worn under the clothes for cramp relief. Over-the-counter douches, creams or sprays cure other minor vaginal infections and irritations. The losing of one's virginity, often accompanied by the breaking of the hymen, usually occurs anytime after menarche begins in the teenage years well before marriage. Intercourse happens at the girl's will without the knowledge or consent of her parents or friends. Again the public appearance of the female may not drastically change, however, sexual activity often constitutes body modifications such as the use of contraceptive methods like the pill, the patch, condoms or a sponge. The wearing of sexier, more adult undergarments is also seen usually in the form of matching bras and panties made of lace, satin or leather in order to entice a sexual partner. The application of sex toys or aids such as lubricants, vibrators, edible underwear or handcuffs are used for similar reasons. All of these may continue throughout the female's adult life. As a result of early defloration marriage comes and goes without significant ritual or change in dress regarding intercourse. Conception often occurs after marriage and usually in the woman's twenties or thirties. If conception is not desired abortions are easily and safely obtained via medical personnel. If a baby is desired, books, classes, the Internet and the doctor or midwife are the main sources consulted and it is the woman's partner, often her husband, who is the most involved and supportive. A shift in the alterations of dress can be seen here, as ingestion, applications or insertions are virtually nonexistent in pregnancy, however, an entire new wardrobe is often purchased and worn for the nine-month period. This includes larger garments, usually of similar female fashions as their non-pregnant counterparts, nursing bras and pregnancy belts. The ritual of throwing the expectant mother a baby shower marks another aspect of dress involved in this life stage, however, this time aiding in the construction of the unborn baby's gender via its clothing and accessories. Pregnancy is also often the only time menstruation ceases for a lengthy period. Menstruation usually resumes to normal between pregnancies and continues until menopause, the conclusion of a woman's reproductive life resulting in the complete eradication of the menses, is reached in a woman's forties or fifties. This change constitutes little alteration in dress except perhaps the application, ingestion or insertion of medication. These modern menstrual stages of dress provide intriguing tools for contrast and comparison to keep in mind when reading about those of ancient Greek women. Of equal importance, however, is the recognition and avoidance of applying "ethnocentric, value-charged terms such as mutilation, deformation, decoration, ornament and adornment" when designating types of historical dress, reminds Eicher and Roach-Higgins.(11) By using this type of terminology we are "usually applying their [our] own personally and culturally derived standards to distinguish the good from the bad, the right from the wrong, and the ugly from the beautiful, and thus inevitably reveal more about themselves [ourselves] than about what they [we] are describing."(12)

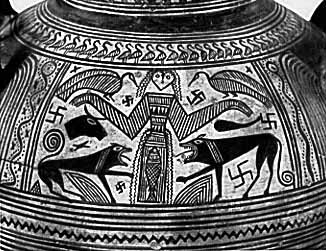

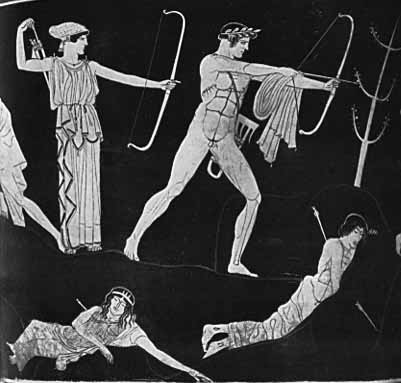

The Cult of Artemis The goddess Artemis, daughter of Zeus and sister of Apollo, took on many names and identities in the Greek world perhaps most famously as the huntress. Artemis also played a major role in female life cycles, especially those that involved bloodshed. The myth of how Artemis obtained this identity proclaims that one day some children tied a rope around a small statue of her and playfully claimed to be strangling it. This was considered sacrilegious and the elders stoned the children to death. The women of the city were then struck with a disease which left their babies stillborn. The citizens consulted the priestess of Apollo who declared the children should be buried and receive annual sacrifices because they had been wrongly killed. From then on Artemis' role as a protector of children, particularly girls, and their various life stages was reflected. Artemis was designated an eternal youth by her father Zeus, meaning that she never reached menarche. This is an ideal example of the ironic duality of the Greeks as she who cannot bleed presides over the bloodshed of others, she who can never give birth chooses to prevent birth in others or provide a successful birth.(13) In most artistic representations of her Artemis is dressed as the huntress indicated by the presence of a bow or arrow in her hand and the wearing of a shorter chitoniskos, or draped women's garment falling just above the knees, common for participation in active sports such as hunting as well as the dress of young girls.(14) An example of Artemis dressed as the goddess of female stages is represented with Aphrodite and Eros on the east frieze of the Parthenon. She is linking arms with Aphrodite signaling the transformation of maidenhood to motherhood as well as the relationship of chastity and sexuality between the two goddesses. Wearing a clinging, pleated chiton, or draped garment, gathered into a protective covering at her genitals, Artemis' right hand holds up one shoulder of the garment as it slips off the other possibly signifying her potential although unrealized sexuality.(15) The cult of Artemis and its ritual of Arkteia, or Bear Festival, usually held at the sanctuary at Brauron, is perhaps the best documented regarding her role in the lives of pre-pubescent girls and dress. The legend of the festival relates to the story of a young girl who was scratched by a bear and who, aided by her brothers, shot it and therefore offended Artemis. As a result Artemis demanded retribution that all the girls in the land must serve her before marriage by dressing as a bear and performing ritual acts at her shrine. All references to this ritual, which was probably meant to represent the transformation of wild, animalistic children into the "mother bear" figure, including texts, vase paintings and Aristophanes' Lysistrata, suggest the girls, called parthenoi, were of varying ages and stages of development from seven to fifteen but who had not reached menarche.(16) Many small, black-figure krater vases have been found at Artemis' shrine and depict these girls in some sort of procession, dancing or racing and often holding twigs or torches at an altar. They are either naked, wearing short yellow-brown colored chitoniskos perhaps dyed with saffron, a popular herb for dying cloth and relieving menstrual symptoms, or suits made from the skins of bears.(17) Some have hair to their shoulders and others have it cut very short. Inventory lists found in Athens regarding this sanctuary suggest that perhaps the yellowish chitoniskos worn by the girls at this coming-of-age ceremony were afterwards dedicated to Artemis. There is some evidence they also dedicated small, inscribed votive statues of females depicting either Artemis or the young girl herself as well as elaborate textiles, both hoping to aid in the coming menstrual flow and subsequent marriage.(18)

Menarche According to all of the medical texts menarche usually began in the girl's fourteenth year, continued to appear usually monthly, hence the Greek term "menses," and indicated that she was prepared for marriage and physically capable of pregnancy. Most of the information regarding the beginning of menstruation and its associated dress practices comes from these medical texts, which more heavily describe the physicality of menses. Classical Greek physicians did not dissect human bodies and of course did not menstruate themselves, however, menstrual blood although originating internally becomes external and therefore accessible to observation and study.(19) Besides this fact these male physicians claimed their findings, including those regarding dress, were often provided by female patients and midwives.(20) Having officially left childhood behind, menstruating females, called gynaikes, although not yet women had entered a new stage in their adult lives constituting various changes in dress. Externally and most obviously the chitoniskos was abandoned in favor of the longer, more modest chiton or peplos. These traditional items of clothing have been found placed in open boxes or used to clothe the statues in the shrines of Artemis. Richly embroidered fabrics have also been found in the shrines probably dedicated to Artemis by the appreciative mother of the menstruating girl.(21) This also appears to be the time when the wearing of the girdle, or zone, began, as younger girls are usually ungirded in artistic representations.(22) The girdle's basic structure resembled a belt tied externally around the waist constructed from a narrow braided band, metal or elaborately embroidered fabric (see the top illustration). Like all textiles they were probably created by women and may have been decorated with symbols of fertility and sexuality although it is possible that the presence of the girdle itself without these embroidered or applied symbols represented the same.(23) Another obvious item of dress was the wearing of an amulet charm of herbs or roots around the neck to alleviate menstrual problems or pains. The medical texts often refer to them as folk medicine or magic in a derogatory or sympathetic way, as we see here in a quote from Science, Folklore and Ideology attributed to Soranus:

Amulets continued to be worn throughout the female's life and depending on the associated herbs were used as contraceptives, abortifacients, good luck or birthing devices.(25) Although the medical texts indicate some uses of menstrual blood in medicinal applications, offerings, agricultural fertilization and magical potions there is not reason to believe that menstruating women always walked around without some form of containment. There is little physical, artistic or written evidence of women wearing undergarments for any reason except for athletic events; however, there are a few stories regarding the use of menstrual containment in the form of linen rags, but how they were attached to the body is unknown. They were called phulakia, meaning "protection against" in Greek, and we hear of them in the story of Hypatia who chose not to marry and, when one of her students fell in love with her, threw a used menstrual cloth in his face.(26) On inventory lists from various sanctuary dedications to Artemis "rags" are listed, yet many scholars disagree that these were menstrual rags but tattered clothing instead.(27) There is also some speculation that wool was used as a pessary, or vaginal insertion, in order to contain menstrual blood, stemming from the fact that the medical texts cite wool fuses with herbs as a medicinal insertion.(28) [The ancient Egyptians seem to have done the same thing; see some hieroglyphics]. The "Illness of Maidens" and Death It may seem peculiar to place a section on death between menarche and marriage, however, it was often around this stage chronologically that suicide among young women in ancient Greece was prominent. Often attributed to the "Illness of Maidens," medical texts mention a type of disease that struck a girl pre-menstruation and could continue until womanhood especially if the female could not reproduce. This was usually due to the "wandering womb theory" in which ancient physicians believed that if a woman did not menstruate or procreate quickly the womb would literally wander the body causing hysteria, pallor, headaches, dizziness, vomiting, nosebleeds, choking and suicidal thoughts. In recent years, however, the concept of a wandering womb has been physically discounted and theorists believe it may be an ancient Greek folk illness due to a female's fear of unwanted menarche, defloration or marriage. Conversely, it can also be ascribed to the woman's trepidation that by not being able to menstruate properly or conceive children she was a societal and familial failure.(29) Dress is attributed to these fears and possible subsequent suicide in two notable ways. Dealing with the lack of menstruation was the application of warm lambskins to the girl's abdomen in order to draw out the suppressed blood of a young girl who has failed to menstruate, instead exhibiting hunger, thirst, vomiting blood and a fever.(30) Other therapies expected to help keep the womb in place consisted of washing, oiling and wrapping bandages around the body as well as vapor baths composed of aromatic substances such as sulphur, laurel or animal excrement placed on hot ashes under a cloth. Myrrh and other scented substances were also thought to have warming qualities and were applied externally to the vagina as a fumigation. It was believed that the womb could be lured downward and thus back to its correct location by the use of the hodos, which utilized sweet scents applied to the vagina while foul smells were inhaled by the nostrils.(31) In the case of suicide the method often employed was strangulation using the female's girdle as a noose. Although hanging evoked horror in Greek society it was a particularly appropriate means of suicide to avoid unwanted defloration or rape as well as the inability to menstruate and conceive as it resulted in no bloodshed thus identifying with the strangulation and bloodlessness of Artemis herself. Evidence of this can be seen in the medical texts, the story of Kylon's daughter Myro, who although ripe for marriage takes off her girdle and makes a noose of it,(32) as well as in Aeschylus' Suppliants, in which the chorus threatens to hang themselves to avoid having sex with men they despise.(33) Marriage and Defloration Ideally defloration of the female came on her wedding night, both events which Artemis presided over. This usually occurred soon after the girl began menstruating around the age of fourteen. It marked an important transition as it indicated not only the female's farewell to maidenhood and the savage realm of Artemis but also her introduction into a new household. Although the ritual of marriage came with its own set of prescribed dress those associated with menstruation, as well as the related bleeding accompanying the losing of one's virginity, are notable. One aspect of the bride's external appearance that may have been related to her menstruation was the wearing of a saffron-dyed veil, again noting the importance of saffron as an important herb in the folk medicine of women.34 As Artemis was the goddess of transitions and a marriage deity both males and females offered her locks of their hair on the wedding night. According to Plutarch, brides in Sparta sometimes shaved their entire head before presenting themselves to their husbands. As the wedding night is the time of defloration, it was this transitional bleeding that Artemis and the releasing of the girdle was associated. The girdle was thought to have been tied in a ritual knot by Artemis that could only be untied by her husband as he undressed her.35 It was also on the wedding night that females dedicated all childhood toys to Artemis at her shrine as a parting to adolescence. An epigraph in honor of Laconian goddess Artemis Limnatis suggests this symbolic gift: Timareta, who is about to marry, dedicated to thee, O goddess of Limnes, her tambourines, a ball she loved, a hairnet that held her hair, and her dolls. She, a virgin, has dedicated these things, as is fitting, to the virgin goddess, along with the clothing of these small virgins. In return, O daughter of Leto, extend thy hand over the daughter of Timaretos and piously watch over this pious girl.(36) Another example of a marriage dedication can be seen here in this kore [I had to delete the illustration], a free-standing stone statue of a young Greek woman usually thought to have been a dedication in sanctuaries of divinities or a funerary marker. This particular kore is noted by its inscription as a wedding dedication of Nicandre, a Naxian woman, to Artemis at her Delos sanctuary. Wearing a snug, belted peplos, the kore has holes in each hand thought to originally have held the metal attributes of a bow and arrow thus identifying her as Artemis. We cannot be sure, however, that the kore does not represent Nicandre herself.(37) Applications, ingestions and insertions of herbal remedies could still be used at this life stage, particularly those aiding in the alignment of the womb and the preparation for conception. In Diseases of Women a series of fertility tests, called peireteria, are noted. One example from this Hippocratic corpus, recounted in an article titled "Menstrual Catharsis and the Greek Physician," states, "If a woman has not conceived and you wish to determine whether conception is possible, wrap her up in a cloak underneath which incense should be burned. If the odor seems to pass through the body to the nose and mouth, then she is not sterile."(38) In the same source fertility could also be diagnosed if a pessary of garlic gave bad breath to the woman the following day. Pennyroyal appears in the same context as a pessary, this time mixed with honey and added to wool because it too exhibits a strong odor. To be eaten for seven days prior to sleeping with her husband, a pennyroyal soup made from flour and wine was thought to aid the woman in conception.(39) Conception and Giving Birth Conceiving children was seen as a wife's main duty and promoted soon after the wedding. Only after giving birth to the first child and successfully dispelling the lochia, or liquid discharge of the uterus after childbirth, had the female finally become a true gyne, or full woman. Women often spent the majority of their childbearing years pregnant or nursing children, both causing the absence of menstruation. Again external dress changed little during these stages.(40) The drape and roominess of the peplos and chiton appears to have easily allowed for the expanded abdomen and breasts of pregnant women. It is after the first child was born to a woman that the absence of the girdle from her dress is seen, the possible reason discussed below. Dealing particularly with societal beliefs about the body, this is an appropriate stage to discuss the Greek reflection of women as containers represented in art. The medical texts make reference to such often citing the neck and mouth of a jug as representing the vaginal opening and the large body of the jug as her internal organs swelling with child.(41) According to Sebesta, just as the wool-basket became a metaphor for wifehood, "the Greeks were fascinated by the image of a pregnant woman containing an unseen baby inside her. Hippocrates likened the womb to a cupping jar. Aristotle speaks of the womb as an oven, and elsewhere we find the female body correlated with a treasure chamber." (42) The use of herbs in various applications once again aided in the internal, private menstrual dress of these stages. Though this section focuses on the promotion of conception and birth as the bearing children was thought to be the desired societal role of women it is noteworthy to mention that there is much evidence of similar body modifications being used as contraceptives and abortifacients in the medical texts. It is unknown how often or successfully they were used as the same herbs used in different ways were thought to both promote conception as well as hinder it and the line between discharging a late menses and an early abortion is unclear.(43) A good example was the use of birthwort, known for its connection to the ancients and childbirth, as a woman nursing a baby with birthwort leaves in the background is found on an Egyptian vase from Thebes. It was often ingested to ease a difficult childbirth but could also prevent that problem altogether with its abortive and contraceptive agents. There is evidence the ancient Greeks knew of this as Galen used it in a recipe for an abortifacient to be drunk and Dioscorides placed it in a suppository with pepper and myrrh to provoke menstruation or to expel a fetus.(44) The same goes for artemisia, the plant named for Artemis and her diverse roles of goddess of forest, woodlands, fertility and childbirth. It was thought to help hasten or assist delivery, stimulate menstruation or remove the afterbirth. Ironically and appropriately artemisia has recently been found to be an effective antifertility agent tying it even more closely to Artemis' duality as the promoter of fertility and infertility in humans and animals alike.(45) In the case of unceasing lochial discharge after giving birth, Soranus writes in Gynecology, as reprinted in Science, Folklore and Ideology, of the use of pessaries:

After the birth of a child the most documented form of change in menstrual dress is seen in the form of dedications to Artemis. This usually occurred in the first few days after delivery as the woman was thought to be impure and thus should remain in the company of her midwife, friends and neighbors and away from her husband until a ritual purification and sacrifice was complete. Artemis once again released the girdle in labor although another married woman physically and symbolically untied the knot. After the successful labor it was dedicated to Artemis once and for all and never worn by the woman, now a full gyne, again. Inscriptions tell us that linens from the birthing bed as well as the clothing of women who died in childbirth were also forms of textile dedications made to Artemis at this stage.(47) Other items dealing with the female body and realm were dedicated to Artemis, such as bronze objects, like this mirror found at Brauron. Thousands of votive statues have also been found in reference to childbirth usually depicting the giver, Artemis, a pregnant female, a male infant or, in one case, two pair of vulvae and a pair of breasts, all inscribed with gratuitous offerings for childbirth.(48) Menopause The evidence regarding menopause in ancient Greece is little, mainly due to the fact that the life span for women was much shorter than it is today, resulting in death prior to menopause. In the available data there is no marked modification in dress. Aristotle and Soranus both believed women reached menopause, the end of menarche and therefore the barrenness of the woman, somewhere between forty and fifty-years-old. Since this information only comes from formal medical texts we do not know how women felt about this change or whether or not they had a name for it.(49) There is evidence that some women who lived beyond menopause were chosen by Artemis as priestesses because of their lack of menstruation. This apparently came from a religious rule which stated that the power to deliver other women's children should be done by those who could not deliver their own. A History of Women quotes Plato's Theaetetus as a valid source for this account, stating that Artemis "assigned the privilege [of midwifery] to women who were past childbearing, out of respect to their likeness to herself."(50) There are some citations of midwives advancing enough to become physicians. Seen here receiving her license on her mid-fourth century funeral monument is Phanostrate, the first woman doctor identified as such in art [illustration unfortunately deleted].(51) This in an important link to our historical readings of menstrual dress and culture in the ancient world as the male authors of the existing medical texts clearly state that they were written either for midwifery use or as a result of midwives' providing the pertinent female voices and facts. Conclusions and Comparisons To the Greek female menstruation marked many of life's most significant stages. Dress and appearance played important roles, from playing the bear at Brauron and wearing protective herbal amulets and rags at menarche to wedding night hair cutting and post-birth textile dedications. Although the visual evidence is weak and we must read between the lines of medical texts and inscriptions to find women's voices the scholarly research is continual and promising. The men's voices, both as artist and author, also provide valuable insight into their interpretations and beliefs regarding menstruation. The reading of this ancient menstrual culture and its dress is key to understanding and identifying the roles that females held both socially and privately throughout their lives and the transformation from young girls to women, brides, wives, mothers and elders. Menstruation is a universal female experience regardless of gender, ethnicity or era thus the knowledge of ancient Greece helps us to comprehend our own menstrual culture. Although evolving, our medical philosophies and texts derived directly from the writings of Aristotle and Hippocrates. Besides the use of recent medical and scholarly writings one wonders if and how our modern menstrual dress and culture will be preserved in the form of art and artifact for future generations. One possible example is the Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health in the Washington, D.C., area. The museum contains collections of the scientific, cultural and dress nature of menstruation and inhabits the wood-paneled basement of founder, director and curator Harry Finley's home in Hyattsville, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Finley has a bachelor's degree in philosophy from the John Hopkins University and a partially completed masters degree in German. In the 1980s he lived and worked in Germany as an art director for a small U.S. government magazine. He is a graphic designer and is currently working [until 1 July 2004] at the National Defense University as a designer for the Department of Defense. It was in Germany that he began collecting print advertisements on menstruation, which led to purchasing the actual products at the grocery store and Ebay and ultimately resulted in donations from major companies [including Tambrands, Natracare, Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble] and private citizens. The collection, now totaling about four thousand objects, makes up the exhibits in the museum Harry started in 1994 after returning to the United States.(52) The museum offers [it closed in 1998, but seeks a public place, preferably in the Washington, D.C., area] a variety of artifacts, information, art, books and devices, many of which are displayed on eight truncated mannequins wearing items of menstrual dress from history such as a 1914 facsimile of a Sears and Roebuck sanitary apron, belts and various underwear (see figure 10). For example, one display shows washable and ecologically friendly pads, tampons and associated gear all created by small companies operated by women, such as Natracare. Other forms of menstrual containment, such as two brands of contemporary menstrual cups, the Instead and The Keeper, and one from the 1970s, the Tassaway, are also exhibited. Historical print advertisements make up another large part of the collection, like Kotex's first ad in January 1921 explaining the pad's origin as a bandage for soldiers in the World War. A more light-hearted side of fashion regarding our menstrual culture is preserved as a dress made of panty liners and maxi pads accompanied by shoes embellished with tampons was the 1995 Halloween costume of a John Hopkins University worker in the laboratory that developed the Instead menstrual cup.(53) Finley has encountered problems, contention and threats as a man in a woman's private world although he does not claim to be an authority on the menstrual culture nor does he claim sole authorship of his exhibits. He includes certified doctors, scholars and women on his board of directors, as the main interpreters in the exhibits and as storytellers on the website. He also provides a detailed provenance of each piece in his collection and continually updates and cites new research, medical findings and writings on menstruation and other issues related to women's health.(54) Prompted by the backlash and his own educational training, Finley presents some ethical dilemmas of collecting and displaying cultural property, especially on such a taboo subject, in his speaking engagements, on his website and in his exhibits. He provides compelling philosophical ideas about who owns or has authority over the menstrual culture. Ultimately the bias against the Museum of Menstruation lies not in the physical museum and its objects but in the idea that menstruation is not a valid topic. It is a theory, oddly enough, promoted almost solely by women. Perhaps we fear Finley is a contemporary Galen or Soranus. Or perhaps, much like our Greek predecessors, we still do not see menstrual dress as culturally valid enough to preserve. By re-examining history and redefining the way we think about menstruation and its associated dress, changing assumptions and extending its application in new and different ways, the Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health, along with scholars, educators, authors and historians, is attempting to reform and revolutionize this bias.(55) Amy Pence-Brown wrote this paper as a student at the University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota, and kindly allowed me to put it on the MUM site. The article is ©2003 Amy Pence-Brown. Footnotes and bibliography are below.

1 Joanne B. Eicher and Mary-Ellen Roach-Higgins, "Dress and Identity," in Dress and Identity, eds. Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins, Joanne B. Eicher and Kim K.P. Johnson (New York: Fairchild Publications, 1995), 7. 2 Judith Lynn Sebesta, "Visions of Gleaming Textiles and a Clay Core: Textiles, Greek Women, and Pandora," in Women's Dress in the Ancient Greek World, ed. L. Llewellyn-Jones (London: Duckworth Publishing, 2002), 132. 3 Eicher and Roach-Higgins, "Dress and Identity," 8. 4 Joanne B. Eicher and Mary-Ellen Roach-Higgins, "Definition and Classification of Dress: Implications for Analysis of Gender Roles," in Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning in Cultural Contexts, eds. R. Barnes and J.B. Eicher (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 13. 5 Janina K. Darling, "Form and Ideology: Rethinking Greek Drapery," Hephaistos 16/17 (1998): 454; Robert Maynard Hutchins, ed., Great Books of the Western World, vol. 10, Hippocrates/Galen, trans. Francis Adams and Arthur John Brock (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1952), ix. 6 Aristotle, History of Animals, trans. Richard Cresswell (London: George Bell and Sons, York Street, Covent Garden, 1887), iv-ix. 7 Soranus' Gynecology, trans. Owsei Temkin with the assistance of Nicholas J. Eastman, Ludwig Edelstein and Alan F. Guttmacher (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), xxiv-xxxii. 8 Hutchins, 163. 9 Helen King, "Medical texts as a source for women's history," in The Greek World, ed. Anton Powell (London: Routledge, 1995), 200. 10 Ibid., 200-210. 11 Eicher and Roach-Higgins, "Definition and Classification of Dress," 14. 12 Ibid. 13 Helen King, "Bound to Bleed: Artemis and Greek Women," in Images of Women in Antiquity, eds. Averil Cameron and Amelie Kuhrt (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1983), 117-125. 14 Charles Seltman, Women in Antiquity (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1955), 93-97. 15 Darling, 63-64. 16 Pauline Schmitt Pantel, ed., A History of Women in the West: I. From Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992), 342-344. 17 Nancy Demand, Birth, Death, and Motherhood in Classical Greece (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 107-113; Seltman, 119. 18 Demand, 87-91; King, "Bound to Bleed," 109-116. 19 Lesley Dean-Jones, "Menstrual Bleeding According to the Hippocratics and Aristotle," Transactions of the American Philological Association 119 (1989): 177-178. 20 Helen King, "Self-help, self-knowledge: in search of the patient in Hippocratic gynaecology," in Women in Antiquity: New Assessments, eds. Richard Hawley and Barbara Levick (London: Routledge, 1995), 135-145. 21 Demand, 88-91. 22 Helen King, Hippocrates' Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece (London: Routledge, 1998), 85. 23 E.J.W. Barber, Prehistoric textiles: the development of cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with special reference to the Aegean (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 257-258. 24 G.E.R. Lloyd, Science, Folklore and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 177. 25 Ibid., 129. 26 Gillian Clark, "Health," chap. in Women in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 77. 27 Demand, 90. 28 Clark, 77. 29 Demand, 55-57, 102-107; King, "Bound to Bleed," 109-121. 30 King, Hippocrates' Woman, 29. 31 Ibid., 36-37. 32 Ibid., 85. 33 King, "Bound to Bleed," 109-19. 34 Sebesta, 135. 35 King, "Bound to Bleed," 109-21; Demand, 88-91. 36 Pantel, 361. 37 Elaine Fantham, et al, Women in the Classical World (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 19. 38 Etienne Van de Walle, "Menstrual Catharsis and the Greek Physician," in Regulating Menstruation: Beliefs, Practices, Interpretations, eds. Etienne van de Walle and Elisha P. Renne (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001), 12. 39 Ibid., 9-7, 12. 40 King, "Bound to Bleed," 121. 41 Van de Walle, 10-12 42 Sebesta, 126. 43 Van de Walle, 3-19; John M. Riddle, Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 35-82. 44 Riddle, 58-59. 45 Ibid., 47-48. 46 Lloyd, 195. 47 King, "Bound to Bleed," 120-125; King, Hippocrates' Woman, 84-6; Pantel, 366-368. 48 Demand, 88-91; Fantham, et. al. 36-38. 49 Clark, 88; D.W. Amundsen and C.J. Diers, "The Age of Menopause in Classical Greece and Rome," Human Biology 42 (1970): 79-86. 50 Pantel, ed., 374. 51 Demand, 68. 52 Harry Finley, Founder, Director and Curator, Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health, email interview by author, Minneapolis, Minnesota, April 29, 2003; Doug Kirby, Ken Smith and Mike Wilkins, "The Museum of Menstruation," roadsideamerica.com: Your Online Guide to Offbeat Tourist Attractions Website, Middletown, NJ, http://www.roadsideamerica.com/ (accessed April 29, 2003). 53 Harry Finley, The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health Website, Hyattsville, Maryland, http://www.mum.org/index.html (accessed September 16, 2003); Finley interview. 54 The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health Website. 55 Karen Warren, "A Philosophical Perspective on the Ethics and Resolution of Cultural Properties Issues," in The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property, ed. Phyllis Mauch Messenger, 2nd ed. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999), Amundsen, D.W. and C.J. Diers. "The Age of Menopause in Classical Greece and Rome." Human Biology 42 (1970): 79-86. Aristotle. History of Animals. Trans. Richard Cresswell. London: George Bell and Sons, York Street, Covent Garden, 1887. Barber, E.J.W. Prehistoric textiles: the development of cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with special reference to the Aegean. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992. Clark, Gillian. "Health." Chap. in Women in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Darling, Janina K. "Form and Ideology: Rethinking Greek Drapery." Hephaistos 16/17 (1998): 447-69. Dean-Jones, Lesley. "Menstrual Bleeding According to the Hippocratics and Aristotle." Transactions of the American Philological Association 119 (1989): 177-192. Delaney, Janice, Mary Jane Lupton and Emily Toth. The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. Revised, expanded edition. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1988. Demand, Nancy. Birth, Death, and Motherhood in Classical Greece. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. Eicher, Joanne B. and Mary-Ellen Roach-Higgins. "Definition and Classification of Dress: Implications for Analysis of Gender Roles." In Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning in Cultural Contexts, eds. R. Barnes and J.B. Eicher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. ________. "Dress and Identity." In Dress and Identity, eds. Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins, Joanne B. Eicher and Kim K.P. Johnson. New York: Fairchild Publications, 1995. Fantham, Elaine, Helene Peet Foley, Natalie Boymel Kampen, Sarah B. Pomeroy and H. Alan Shapiro. Women in the Classical World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. Finley, Harry, Founder, Director and Curator, Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health. Email interview by author, Minneapolis, Minnesota, April 29, 2003. Finley, Harry. The Museum of Menstruation and Women's Health Website. Hyattsville, MD, http://www.mum.org/index.html (accessed September 16, 2003). Hutchins, Robert Maynard, ed. Great Books of the Western World. Vol. 10, Hippocrates/Galen, trans. Francis Adams and Arthur John Brock. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1952. King, Helen. "Bound to Bleed: Artemis and Greek Women." In Images of Women in Antiquity, eds. Averil Cameron and Amelie Kuhrt. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1983.16-17. ________. Hippocrates' Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece. London: Routledge, 1998. ________. "Medical texts as a source for women's history." In The Greek World, ed. Anton Powell. London: Routledge, 1995. ________. "Self-help, self-knowledge: in search of the patient in Hippocratic gynaecology." In Women in Antiquity: New Assessments, eds. Richard Hawley and Barbara Levick. London: Routledge, 1995. Kirby, Doug, Ken Smith and Mike Wilkins. " The Museum of Menstruation." roadsideamerica.com: Your Online Guide to Offbeat Tourist Attractions Website. Middletown, NJ, http://www.roadsideamerica.com/ (accessed April 29, 2003). Lloyd, G.E.R. Science, Folklore and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. McLure, Laura K., ed. Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002. Pantel, Pauline Schmitt, ed. A History of Women in the West: I. From Ancient Goddesses to Christian Saints. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992. Riddle, John M. Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. Sebesta, Judith Lynn. "Visions of Gleaming Textiles and a Clay Core: Textiles, Greek Women, and Pandora." In Women's Dress in the Ancient Greek World, ed. L. Llewellyn-Jones. London: Duckworth Publishing, 2002. Seltman, Charles. Women in Antiquity. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1955. Soranus' Gynecology. Trans. Owsei Temkin with the assistance of Nicholas J. Eastman, Ludwig Edelstein and Alan F. Guttmacher. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. Van de Walle, Etienne. "Menstrual Catharsis and the Greek Physician." In Regulating Menstruation: Beliefs, Practices, Interpretations, eds. Etienne van de Walle and Elisha P. Renne. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001. Warren, Karen. "A Philosophical Perspective on the Ethics and Resolution of Cultural Properties Issues." In The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property, ed. Phyllis Mauch Messenger, 2 nd ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999. The article is ©2003 Amy Pence-Brown. © 2004 Harry Finley. It is illegal to reproduce or distribute any of the work on this Web site in any manner or medium without written permission of the author. Please report suspected violations to hfinley@mum.org |